As civil plaintiff attorneys, we’re taught a basic rule:

Don’t ask your own client questions during their deposition.

It’s not the time. Save it for trial, when it matters.

Let the defense ask.

Let them posture.

Let them try to score points.

But lately, I’ve stopped playing by that rule — because something more important is happening in the room.

When preparing sex abuse clients for a deposition, I can’t always prepare them for the cruelty of the questions they’ll be asked.

A sex worker in one of our cases— who had been violently assaulted — was asked, completely out of the blue:

“What kind of pole do you like dancing on?”

The defense attorney smirked. Like it was clever.

It wasn’t.

It was an act of humiliation.

It had zero relevance to the legal claims.

It was just about putting the plaintiff back in her place.

Another client — a woman violated during what was supposed to be a healing massage — was asked her bra size.

Let me repeat that.

She was assaulted. And then asked, in a legal proceeding:

“What size bra do you wear?”

Another client, a police officer, was asked whether she used de-escalation techniques while being sexually assaulted by another officer.

Because apparently, she was supposed to talk him out of it.

These questions weren’t about truth-finding.

They were power plays. Designed to belittle, embarrass, and retraumatize.

And let’s be honest — they’re not rare.

They’re a strategy.

One that defense firms continue to deploy because they think it works.

So I decided to change things up.

At the end of these depositions — after the invasive, sexualized, degrading questions have landed — I now ask the clients a question of my own.

I don’t know the exact answer they’ll give.

But I know it will matter.

I ask:

“How did it feel when the defense attorney asked you that?”

They answer:

“I felt small.”

“I felt dirty.”

“I felt like I didn’t matter.”

“It reminded me of the first time I was assaulted — when no one believed me then, either.”

But then something shifts.

Because in answering that question, the client gets something they haven’t had for most of their case —

Control.

They get to speak directly to the tactics being used against them.

They get to name what was done to them — not just by the original perpetrator, but by the legal system that supposedly exists to help.

And almost every time, they say the same thing afterward:

“Thank you. I needed that.”

“I feel stronger now.”

“It felt good to say it out loud.”

Let’s be clear:

This doesn’t fix what happened.

It doesn’t make the courtroom (or the conference room) safe.

But it’s a start.

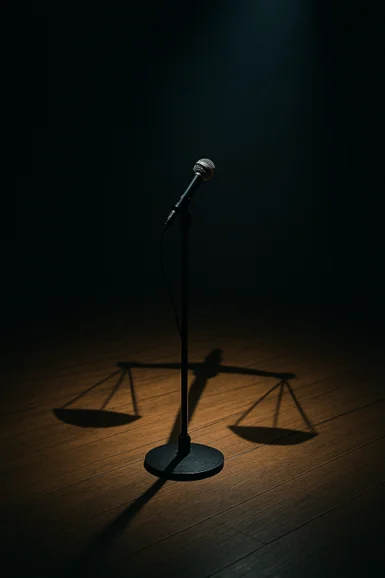

Because sometimes, the most powerful thing we can do as civil attorneys isn’t to shield our clients from harm — it’s to give them a sword and a microphone and let them swing.

So as we mark Sexual Assault Awareness Month — when the teal ribbons come out, and the corporate statements start flowing — I’m asking you to do more than raise “awareness.”

Raise hell.

Call out the cruelty masquerading as cross-examination.

Push back when “strategy” looks like degradation.

Make space for survivors to speak their truth, even when it makes the room uncomfortable.

And if you’re a fellow civil litigator:

Break the rule.

Ask the question.

Let your client answer.

Let them take some of their power back.