By Furhad Sultani & Kristin Michaud

In honor of Indigenous Peoples Day (October 9, 2023) and the upcoming 50th anniversary of the 1974 Boldt Decision [1], we are shining a light on the historic impact that landmark court decision had in righting the wrongs of history. This decision reiterated what was promised to the Indigenous peoples in (what is now) Washington state in the 1855 Treaties – equity, inclusion, right to sustenance, and practice of culture as it had been since Time Immemorial.

Throughout his ‘treaty tour’ of 1854-1855, Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens presented treaties to Indigenous bands and groups. These treaties often included language that in ‘exchange’ for ceding all their lands to the US Government, Indigenous peoples were allowed to continue to fish ‘in their usual and customary’ stations…and in common with all citizens of the Territory.” [2] The primary reason for this was obvious – the US Government didn’t want to expend any funds to feed them when they were forced onto reservations. In the early 1900, non-Indigenous businessmen, seeing a profitable industry in Washington’s waters, pushed the Indigenous fishers out of their usual fishing stations. From that point on, Indigenous fishers were subjected to intimidation, destruction of nets/traps, and often with brutal physical assaults at the hands of non-Indigenous persons, law enforcement, and State wildlife officials.

By the early 1960s, Indigenous peoples were holding “Fish In’s” and other protests to assert their lawful rights afforded to them under the Stevens Treaties. Activists such as Billy Frank, Jr. [3] (Nisqually), Don McCloud [4] (Puyallup), and Alison Bridges [5] (Puyallup) led efforts pressuring the U.S. Government to force States to comply with treaty provisions and prevent interference in exercising those treaty rights by State wildlife officials and non-Indigenous citizenry. The initial Complaint was filed in the Western District of Washington in September 1970 on behalf of the Hoh, Makah, Muckleshoot, Nisqually, Puyallup, Quileute, and Skokomish Tribes. Lummi, Quinault, Sauk-Suiattle, Stillaguamish, Upper Skagit, and Yakama would eventually join them.

(Of note: Lester Stritmatter, a founding member of The Stritmatter Firm and the father of current Senior Partner Paul Stritmatter, represented the Hoh Tribe in this case.)

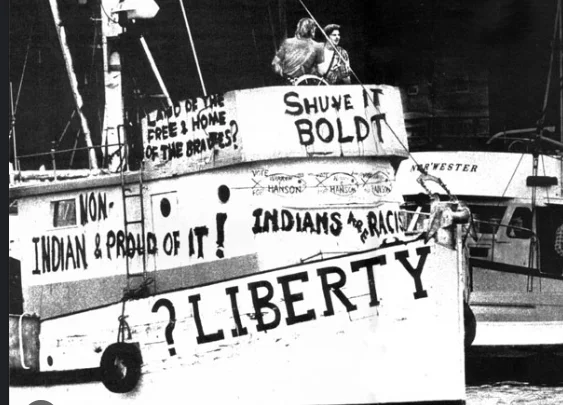

On February 15, 1974, Judge Hugo Boldt issued his opinion affirming signers of the Stevens Treaties the right to 1) take fish at the ‘usual and accustomed’ stations, 2) to equally share the resource ‘in common’ with non-Indigenous citizens of Washington state, and 3) work in conjunction with the State in the management of these fisheries (or resources). The State immediately appealed Judge Boldt’s decision. His decision would be upheld by the US 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in 1975. The United States Supreme Court declined further review.

Despite this milestone for Indigenous peoples and treaty rights, US v. Washington (through sub-proceedings) continues. To learn more about the ongoing legal struggle case and to read substantial court orders, please visit the USDC of Western Washington, Special Cases page, which can be found here: Special Case Notices | Western District of Washington | United States District Court (uscourts.gov

[1] U.S. v. Washington, 384 F. Supp. 312 (1974). United States v. Washington, 384 F. Supp. 312 (1974) | Caselaw Access Project

[2] Article III. Treaty of Medicine Creek, 12/26/1854. Medicine Creek Treaty, 1854 | Nation to Nation (si.edu)

[4] https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/fish-ins.htm

[5] https://nwifc.org/fishing-rights-activist-alison-gottfriedson-passes-away/